AbstrAct

Topical fluoride treatment prevents dental caries. However, the resulting calcium-fluoride-like deposits are soft and have poor wear resistance; therefore, frequent treatment is required. Lasers quickly heat surfaces and can be made portable and suitable for oral remedies. We examined the morphology, nanohardness, elastic modulus, nanowear, and fluoride uptake of fluoride-treated enamel followed by CO2 laser irradiation for 5 and 10 sec, respectively. We found that laser treatments significantly increased the mechanical properties of the calcium-fluoride-like deposits. The wear resistance of the calcium-fluoride-like deposits improved about 34% after laser irradiation for 5 sec and about 40% following irradiation for 10 sec. We also found that laser treatments increased fluoride uptake by at least 23%. Overall, laser treatment significantly improved fluoride incorpo-ration into dental tissue and the wear resistance of the protective calcium-fluoride layer.

KEY WORDS:laser therapy, dental enamel, flu-orides, mechanical phenomena, nanomedicine, scanning electron microscopy.

Introduction

Many studies have reported that fluoridation provides a cost-effective means of preventing dental decay (Ripa, 1990). Fluoridation can be achieved via a dentifrice, water fluoridation, or topical fluoride treatment. The effectiveness of a dentifrice requires good dental hygiene habits, and water fluoridation risks fluorosis (Szpunar and Burt, 1988; Marinho et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2010). Therefore, topical fluoride treatment is preferred by many dental practitioners. Children, as well as adults undergoing orthodontic treat-ment, especially need topical fluoride treatment. However, the calcium-fluo-ride (CaF2)-like deposits generated on the enamel surface during treatment are generally eroded away within days or weeks as a natural consequence of eat-ing and chewing (Øgaard, 2001). Jeng et al. (2008, 2011) discovered that the hardness and elastic modulus of the CaF2-like deposits were approximately 0.77 and 53 GPa, respectively, while the wear depth was about 5 times higher than that of native enamel. Therefore, methods are required to increase the wear resistance of these deposits to improve the long-term effectiveness of the treatment.

A laser was first used in dentistry, in the 1960s, by Stern et al. (1966), who showed that using a ruby laser to irradiate dental enamel significantly improved its resistance to acid. Since then, many other forms of laser irradia-tion have been shown not only to improve the acid resistance of enamel, but also to increase fluoride uptake on the enamel surface (Yamamoto and Sato, 1980; Nelson et al., 1986; Featherstone et al., 1998; Hsu et al., 2004). Of the various forms of laser systems available, the pulsed CO2 laser is one of the most appropriate for dental health care applications (Rodrigues et al., 2004). Because the wavelengths of visible and near-infrared laser systems (e.g., Ar and Nd-YAG lasers) are only weakly absorbed by enamel (Gonzalez et al., 1996), high irradiation intensity is required to achieve the desired effect, and thus the risk of damaging the underlying pulp increases. In contrast, CO2lasers have an infrared wavelength that is readily absorbed by the enamel surface. Consequently, the scattered energy is very low, and the laser irradia-tion energy is confined to the enamel surface. Furthermore, the use of a pulsed irradiation technique minimizes the accumulated energy within the enamel surface, which further reduces the risk of thermal pulp damage (Kantorowitz et al., 1998).

dental laser

results

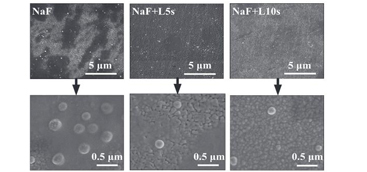

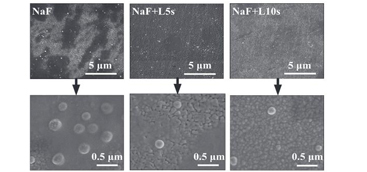

The Table summarizes the results obtained for the surface roughness, nano-hardness, elastic modulus, and mean wear depth of the enamel surfaces sub-ject to laser exposure with or without topical fluoride treatments.

discussion

Previously, we reported that clinical fluoride treatment gener-ates fluoride-containing deposits only hundreds of nanometers thick (Jeng et al., 2008, 2011). However, clinical evidence (Lowndes et al., 1996; Ishikawa et al., 2002) has confirmed that even a layer this thin is significantly protective, because it con-tributes to the enamel’s ability to resist cariogenic challenges. The nanometer coating significantly affects various physical, chemical, and even biological properties of the bulk materials, which suggests that the potential contribution of nanocoating to biological systems should not be overlooked. Studies of the effects of nanotribological properties on overall materials per-formance showed a 34% increase in the wear resistance, and CO2 lasing is anticipated to improve that percentage (Bhushan et al., 1995; Bhushan, 2007; Szlufarska et al., 2008).We report here the first nanotribological mapping of fluoride treatment deposits and the enamel from the surface to the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ) with integrated in situ chemical composition analysis, which provides comprehensive biomechanical-chemical insight into the clinically observed protective effect of tradi-tional fluoride treatment and into its potential limitations (Jeng et al., 2008, 2011). Lasers are among the most effective and clinically acceptable approaches for the treatment of various conditions (Miller and Truhe, 1993; Gupta and Kumar, 2011). In this study, we combined lasers with topical fluoride treatments to improve this nanomechanical clinical practice.In addition, we found that the enamel sheaths on the tooth surface shrank after they had been irradiated and were shorter than the central enamel rods (Appendix Fig. 2). This was expected because the sheaths have a relatively higher protein content than rods (Ge et al., 2005) and protein decomposes rap-idly because of the intense heat generated by laser irradiation.